For founders considering selling their company: key factors & a timeline for M&A

I’ve recently been a part of a few M&A processes for companies with whom I work closely. These transactions have been private companies selling to larger companies (public and private) and were all-cash transactions, although we are not strangers to the full range of M&A at Acrew.

This served as inspiration for me to chronicle best practices and considerations for founders who are selling their company. In doing so, I hope that founders read this and take away at least one useful insight. I am grateful and fortunate to have been able to solicit input on this article from several individuals including from Theresia Gouw and Mark Kraynak, a few of my partners at Acrew, Ed Zimmerman and Meredith Beuchaw from the law firm Lowenstein Sandler, Shan Aggarwal, VP Corp Dev, Coinbase, and Art Levy, Chief Strategy Office at Brex. I hope to also hear from more founders as they read through this.

Firstly, some observations:

(1) M&A can be a great outcome for all parties, most of all start-up founders and the team that’s been essential to building. Founders may face conflicting emotions when considering selling their company. That is perfectly understandable; in the beginning many founders hope to build what will be an enduring company. And even so, it’s important to acknowledge that there are plenty of good reasons to sell, which can include: joining a “larger rocketship” (1+1=3), a strong match with an acquirer, burn-out amongst the team, team and investor needs for liquidity, and many other reasons. Further, myriad long-term, stand-alone companies have been founded by founders who sold or exited in some form their prior companies. And don’t forget, many companies who go public successfully can even, down the road, be acquired by a larger company (e.g., Slack). For a founder who sells her company, M&A can be one more step along the entrepreneurial journey.

(2) One way for founders to frame a M&A process is that it’s a continuation of what founders already do. Founders are always selling their company (to customers, partners, investors, and employees).

(3) In times of macro downturns, think of M&A as a game of musical chairs. The companies that test the market earlier in the cycle (before things have gotten particularly bleak), tend to get better outcomes.

(4) As in (3), in markets where incumbents are playing catch-up, there is a window where a few companies will get bought, and by the time those settle, the rest will likely decide to build (vs buy)

With that context, here are the things to consider during M&A:

(1) Getting to know acquirers before a process

It’s always preferable to have pre-existing relationships with acquirers. The most attractive offers tend to come to companies organically based on prior business relationships and partnerships. This is easier said than done. Firstly, I don’t know too many founders who a priori think about getting bought by a specific set of acquirers. But it’s worth the thought exercise. Potential acquirers are often either good partners or competitors. One of the many plates a CEO should be spinning while running their company should be to keep the heat on accretive partnerships. This should be helpful irrespective of whether a founder decides to sell. Further, some engagement with competitors (e.g., at trade shows and conferences or otherwise) can also be helpful.

(2) Ensuring multiple acquirer conversations

The best M&A outcomes typically involve a few potential acquirers who get to later stages (i.e., discussions about price). Timing conversations so they move along at similar paces also matters. If one party moves faster, you can use that as a way to speed up other parties. When you’re single threaded, you introduce considerable risk to your process. Even in an instance where you receive an inbound offer from a highly motivated potential acquirer, having other parties engaged should be best practice. It only takes a solo potential acquirer one time where they miss a deadline you set for them where they realize they are the only ones in a process.

To this end, advisors can help at this stage. Bankers can help drum up additional acquirers. It’s easier to engage a banker sooner rather than later in the process. Another helpful guide for founders during M&A can be a personal advisor who has been through M&A as an operator before. Sometimes this can be one of your investors or board members. Or, alternatively, it can be an advisor well versed in corporate development or even another founder who has recently gone through a M&A process.

If you receive any pushback on running a process from any of your potential acquirers, you can always fall back on reminding them that you have a board plus investor stakeholders to manage and, furthermore, you yourself have a fiduciary responsibility to the company (assuming you are on the board) to get market feedback on pricing and terms.

(3) Selecting an acquirer

At some point, you’re going to have to decide on an acquirer. You, your team, and your board/investor group will want to consider a variety of factors. Occasionally, founders will have the luxury to choose among acquirers and can take into consideration which company will give their product and team the best shot at continued operational growth and success. It’s relatively rare, though, that founders will be able to operate as they did before. Acquirers have a broader set of plans at play. In most instances, founders will have to understand that they are selling and will become an employee. Founders need to introspect as to whether they can spend 1, 2, 3+ years at the acquirer and consider what they might receive in return (financial reward, good landing/outcome for the key stakeholders, continued employment and reward for team members, etc.)

In addition to those considerations, in this volatile macro environment, certainty to close is paramount to consider. As we discussed, these M&A processes can be long, and so the last thing you want is for a transaction to be far down the road and for the company to be low on cash and for the deal to fall through or get re-traded. It is not uncommon to take a lower price with a higher certainty to close, within reason.

To this end, it’s critical to understand why an acquirer wants to buy your company. Is your company getting bought for its product, business, or team (most often an “acquihire”)? Do you understand well your relative position in the negotiation? For example, are there other options on the market (including a build internally) that the acquirer could pursue?

Other factors to consider include:

*The process to close (i.e., approval process). What does the decision making process and timeline look like?

*The relative weights of the different stakeholders with whom you are dealing. Who is your sponsor in the product or business organization? How much visibility does this acquisition have at the executive and board level for the acquirer? How empowered is corporate development and have they (the specific team) been involved in many deals before. Do you have confidence that the parties you are dealing with (e.g., corp dev, product/business champion, key executives, etc.) are feeling settled in their roles? This piece can be hard to suss out, so you’ll have to use your intuition, but you likely don’t want your key champions to leave mid-way through your acquisition process.

*Any other positive or negative incentives at play (team-based, product-based, financial, investor-based, etc.) For example, if you are selling to a public company whose stock has been hammered (as many have of late), consider what the impact might be on their willingness to, say, negotiate on price. Further consider what their willingness might be to pay cash versus stock.

*The Integration Plan: This tends to be overlooked in the M&A process, where the key focus is on deal terms. Founders and their teams will want to pay attention to how they fit into the broader company they are joining.

(4) Putting corp dev on speed dial

Once you’ve evaluated certainty to close, understanding Corp Dev’s M.O. is important. We’ve been in transactions where it’s the first corp dev led acquisition for a large company. This can create friction because when a company hasn’t built the organization muscle of acquiring other companies, it’s likely that the playbook is being built on the fly and even more likely that the integration will also be some what ad hoc. Further, with new corp dev teams, it’s also hard to understand how they will behave because there isn’t a referenceable list of founders to whom you can. In either case, corp dev will likely be an important part of the triangle of influence at the acquirer that is: corp dev, your internal stakeholder / product leader, and the executive team/board.

(5) Dealing with legal eagles

Understand the dynamic between internal GC (should there be one) and external counsel. If there is a formidable legal team on the side of the acquirer, it’s advisable to reference that team if you can. We’ve had instances where we’ve been on the other side of lawyers (law firms) who ask for legal terms that we understand are off-market (e.g., certain indemnity clauses, onerous founder re-vesting, etc.) You will hope that the external counsel will be well versed in helping the acquirer buy venture-backed companies (including tax considerations), as opposed to, say, private-equity backed companies, or even bootstrapped companies. Why? Venture capital is buying minority stakes and you’ll often have a diversified cap table. Hopefully your investors are aligned in their incentives, however, there will always be differences and different firms will have invested in your company at different times. In either case, opposing counsel can make your life quite difficult. That’s also why it’s important to work with legal counsel on your side who is well versed in M&A and has a recent slate of processes they’ve been a part of.

There’s a negotiation that happens back and forth around what is “market”. Ultimately the terms are somewhat of a function of how much leverage each side has, but it will make your job a lot easier if you work with a law firm that can credibly claim to be in market with consistency.

The last point on this, though, is that even legal issues can often be resolved between business stakeholders. It’s give and take and it’s ultimately your job to manage all the parties, including in the legal process. Collect information, get good counsel, ask other founders and investors, and use your judgement.

(6) Keeping your team motivated and momentum going

The best processes will be run on the on the founder side with a small set (i.e., not all) of the founders and exec team. A banker can be helpful on the sell-side (i.e., on your side) as discussed as well. Our general advice is to provide minimal exposure of the M&A process to the team in order to minimize distraction. The extent to which founders stray from that is case by case. This said, team members and employees may well want transparency, particularly around runway. To the extent you think you need to read folks in, use your best judgement, balance your optimism (or pessimism) on the process with keeping the team focused on the business at hand, and consider using specific tactics where needed to retain key talent (e.g., stock awards tied to a M&A outcome). On the last point, once you have a term sheet (as in raising venture money too), your 409A is invalid. One solution to this is to negotiate, as part of the term sheet, new incentives for employees at deal closing. If that doesn’t work with the acquirer, you can also carve out cash bonuses to employees, though this will reduce the deal price for the full cap table.

(7) Managing your investors

Not dissimilar from your employees, you will want to communicate with at least a subset of your investors, as is consistent with the confidentiality agreement your company has signed with an acquirer. Your board should be kept in the loop through the process. They can help field new acquirers and it’s important to remember they too have obligations, as per corporate law, to conduct a proper process. Board members can help create competitive and timing pressure. They can be the group you blame for not conceding on terms for which an acquirer is asking. And they can help get other investors on side. It’s important to check with your counsel as to what the communication cadence needs to be to each of your shareholders, investors, as well as to major third parties whose consents might be required as a condition to or simply as a result of the deal. There is generally a sequence of events that trigger communication with your board, and then another sequence of events that triggers communication with your larger investor group. You also want to understand what the approval thresholds look like (i.e., who do you need, from which class of stock and/or other securities, to approve a transaction). Note that buyers will often ask for an approval threshold higher than what is required by your company’s governing documents.

(8) Driving to close

Like any fundraising or sales process, you have to keep the pressure on. There are a variety of tools to do so. But the key thing to highlight here is that once you’ve decided to sell the company and decided on a price, it’s in your interest to close as soon as readily possible. Time kills deals and time (in a macro downturn) only introduces more risk to close. To the extent an acquirer comes up with new diligence findings or there is a change in the market, it is possible that the acquirer will re-trade the headline price and other key terms. As the process continues, you’re likely consuming cash. And proceeds are going to be net of your cash, so the sooner your close, the better for all.

Speaking of driving to close, now let’s look at the key steps of a M&A process

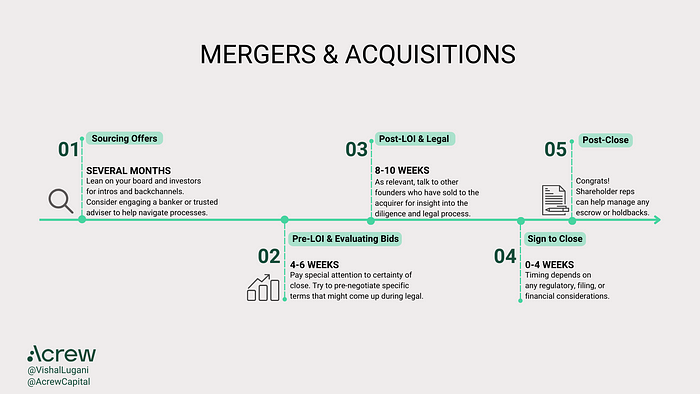

From a timing point of view, founders should plan for up to 9 months to conclude a sale process.

That isn’t to say it can’t happen sooner, but we would counsel that amount of cash buffer. In the world of start-ups, this may require companies to raise a bridge financing and/or consider making cuts to operational burn. As one of my partners counseled, “Every week you wait to cut spend makes the cuts you will need hurt that much more.”

Sourcing Offer(s)

- This entails months+ of relationship building. Immediately ahead of a process, this could take several weeks to a few months to get all parties engaged and doing work

- You’ll want to socialize this with your board and key investors as well, to make sure you’re atop all governance requirements

- Along the way, there are benefits to building relationships with bankers as well, because they are in market and talking to acquirers frequently. This will help you stay top of mind within your industry and get included in everything from conference invites to market maps

Pre-LOI and Evaluating Bids

- Again, this can take several months. A highly motivated acquirer who is running a tight process should be able to get through diligence in 2–4 weeks. But that would be fast in any market. You need to account for competing priorities at the acquirer, any other deals that might come up for their corporate development, and personnel schedules (e.g., holidays, vacation, to name a few)

- Your leverage declines after you sign a LOI; in many cases the LOI puts you into exclusivity with the buyer for a set period of time. So the more specificity you can get on terms upfront, the better

- Consider getting representation and warranty insurance (“RWI”). This will factor into how much of the deal consideration with an acquirer is paid up front vs how much is “at risk” where the selling shareholders will be at risk of losing proceeds earmarked or distributed to them

Post-LOI Confirmatory Diligence & Legal

- Generally diligence here should be less strategic and more operational. Legal diligence, however, will be exhaustive and you may find that more detailed terms are being either negotiated or re-negotiated via the definitive long form deal documents. It’s important to plan for this process with your legal counsel

- If you opted for RWI, the insurer will also be diligencing the company

Sign to Close

- You will then get to a final purchase agreement most often in the form of the merger agreement and collect all the required signatures, including the shareholder approvals

- Signing and closing usually have a gap of at least a few weeks. At the point of signing, you’ll have secured all the approvals from both sides. Timing to close will depend on whether there are any regulatory, filing, of financial considerations that will cause the process to continue on. We advise our founders to ultimately focus on when the cash is in the bank, so to speak.

Post-Close Integration

- Consider having a shareholder representative manage post-deal claims and pay-outs for whatever cash is held back in escrow or as a holdback with RWI

- This is your time to ramp up and focus on the execution plan. If this was a good match between companies, a lot of value can be created here

In conclusion

Not all companies are best positioned to be stand-alone. And that’s more than okay. Further, many founders will exit and then come back and build very successful second or third or fourth companies. Good luck as you navigate this environment and thanks for reading. I’d welcome any and all feedback.

For more about us at Acrew, see our website here.